Celebrating holly (Ilex aquifolium)

December 16, 2024

Learn why there is more to holly than meets the eye.

Some folklore has considered it quite unlucky to fell a holly tree – with that in mind, it stands to reason it must be quite lucky to do the opposite. Here’s hoping all the young holly trees planted during our Silvopasture tree planting project have brought luck to the pastures; or, failing that, will create a lovely hedgerow – which, in itself, is a lucky thing for wildlife.

This spikey (but not always – more on this later…) species of evergreen, is not just a support for wildlife, but to some creatures its presence is essential. Caterpillars of the holly blue butterfly and holly tortrix micro-moth feast on the leaves, while the berries provide a high energy autumn/winter food source for birds and small mammals. So valuable are these berries, that mistle thrushes have been known to viciously guard them from other birds. Unfortunately, these little red berries are toxic to humans, so they are an unsuitable target for foraging – especially if a mistle thrush is in the area!

Holly hedges aren’t just a food source, but a habitat and a home as well. The dense cover is ideal for sheltering nesting birds, while the leaf litter it creates is a snug hideaway for hedgehogs, small mammals and invertebrates of all sizes.

A fascinating little fungus, the holly parachute, is very picky about its home – it will only grow on the fallen leaves of holly. Though considered widespread in the UK, it can be quite a rare find due to its tiny size (the caps are only around 5mm!), and refusal to grow where its namesake plant doesn’t.

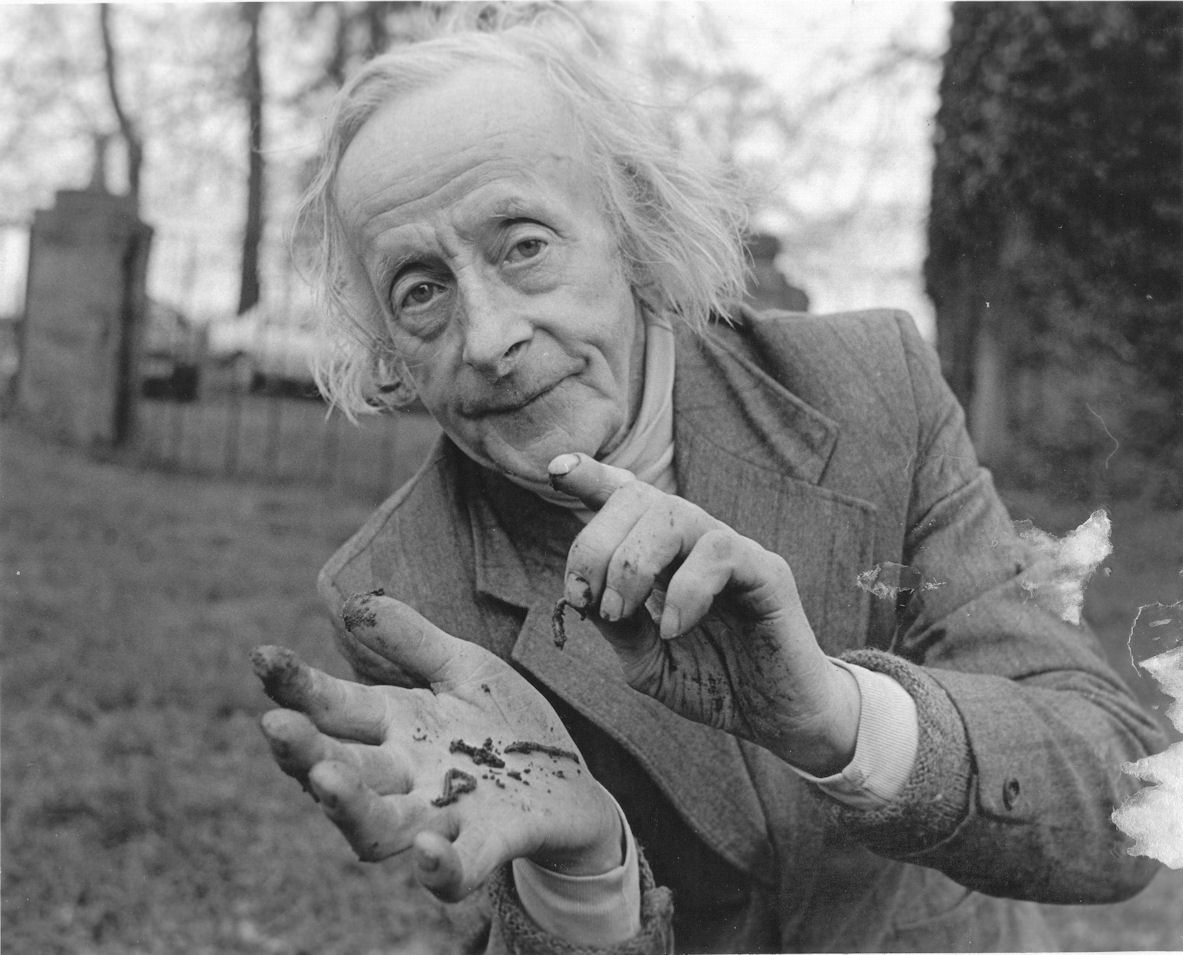

Holly itself, it would seem, is a little more adaptable than its miniature fungal friend – in terms of self-defence anyhow. While known for being prickly, with even its Latin name referring to ‘pointed leaves’, some holly leaves remain smooth. Creating prickles is a way of creating an armour –a response to hungry critters nibbling away at the foliage. It is known as an ‘epigenetic modification’ – where gene expression is altered with no change to the actual DNA itself.

Spikey and smooth alike, the individual leaves (assuming they aren’t munched on) persist on their stem for two to three years in total. When shedding occurs, they are slow to decay, producing those delicate leaf ‘skeletons’ resting amongst the leaf litter. A cycle which, if the folklore is heeded and the holly is left to grow, will continue for the tree’s 300-yearlife span.

Francesca Lant, Marketing and Communications Officer